- Despite much-needed progress having been made in the form of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, there is no evidence that the new legislation will attempt to harmonise the disparity between the many sets of civil proceedings which domestic abuse cases can encompass.

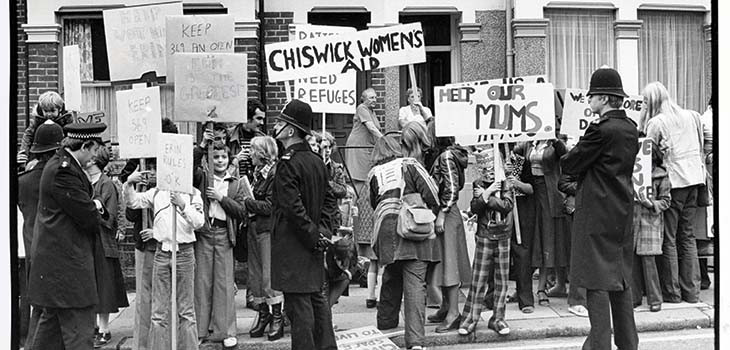

In 1971, Erin Pizzey set up the first domestic violence shelter in England, and perhaps in the modern world, called Chiswick Women’s Aid (today known as Refuge). 50 years later we have the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (DAA 2021) which received royal assent on 29 April 2021. Introduction of this Act was accompanied by a variety of official regrets for the manifest continuing evidence of domestic abuse. DAA 2021 was preceded by the Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act 1976 (on the back of Pizzey’s work) and Pt 4 of the Family Law Act 1996 (FLA 1996). Tucked away in the children part of Family Procedure Rules 2010 (FPR 2010) PD 12J there is, in a mere practice direction, a form of definition of domestic abuse for family proceedings.

Now, there is a new development in the domestic abuse field. Men—mostly wealthy men—are using the majesty and expense of defamation proceedings in the Queen’s Bench Division (QBD) as a yet further means to control their (former) partners. They employ the legal paraphernalia that the QBD involves, including estimated 12-day trials, with case management and preliminary issue hearings; and, of course, wigs and gowns for judges and many of the advocates. Domestic disputes are there ‘resolved’ (‘dispute resolution’ has come to be a euphemism for trial and to adjudication of a case).

Defamation in this context becomes—or can become—a sort of domestic SLAPP (a strategic lawsuit against public—or here, private—participation) for better-off men. Substantial damages can be claimed in such cases as a further form of real (judicially sanctioned?) controlling and coercive behaviour. Surely if a family relationship (and there are plenty of statutory definitions of a family and ‘persons connected’) is involved, by definition the case should go to the family court?

These reflections on the modern law of family breakdown, or a part of it, arise from my brief involvement in Lee v Brown [2022] EWHC 1699 (QB), [2022] All ER (D) 46 (Jul) before Mrs Justice Collins Rice, which exhibited a sort of Johnny Depp II syndrome in the claimant Mr Lee. As a rule, I try to operate a self-denying ordinance: that is, I do not comment on cases I am, or have been, involved in. That said, I must confess to have lived a sheltered life. I have only become aware of the ‘Depp syndrome’ from this case. Collins Rice J dismissed Mr Lee’s claim and adjourned Ms Brown’s counterclaim in assault, battery etc to the county court.

Parallel non-molestation order proceedings

In parallel proceedings to all this, Ms Brown had issued a non-molestation order application in the family court which, after she had been granted two interim orders, was thrown out by a deputy district judge. I am told the deputy district judge refused to read the defamation pleadings. For a variety of reasons that case is on appeal in the family court and is sub judice.

The Civil Procedure Rules 1998 (CPR 1998), nearly 25 years ago, unaccountably—at least to me—ghettoised (that is not too strong a word) away from mainstream civil proceedings each of family cases, insolvency and Court of Protection proceedings (CPR 2.1(2)). This is notwithstanding that rules in each of these jurisdictions regulate the same common law and often the same statutes (eg the Human Rights Act 1998, the Senior Courts Act 1981, the Administration of Justice Act 1960, the Civil Evidence Acts and many others).

A case study

Angela is not married to her partner and cohabitant Bernard. She says she has been subject to domestic abuse, including controlling and coercive behaviour. She wishes to seek protection from the court, any court which can provide her with injunctive relief. Whether or not she is living with Bernard or now separated from him, she can apply (at present) for a non-molestation order; or if the couple are still living together, for an order which excludes Bernard from their shared accommodation. Application(s) are under Pt 4, FLA 1996 in the family court. These proceedings are regulated by FPR 2010. As an aside: if they jointly own a house and Angela or Bernard want to realise their share, their application is separately—as the law now stands— under CPR 1998).

Angela is advised that, if she wishes, she can also claim damages in the county court. This is a separate application, in a court distinct from the family court and a separate set of procedural rules. The civil courts, since 1999 (when CPR 1998 came in), have a different administration from family cases. And then, in the case study, Bernard, who has received an unexpected legacy, and who is suffering at loss of control over Angela, issues a QBD defamation claim. Angela has posted derogatory remarks on Facebook and on a Twitter account. This proceeds under CPR 1998, and not in the county court but in the High Court. The police contemplated a Protection from Harassment Act 1997 prosecution in the magistrates’ court on Bernard’s complaint against Angela, but in the end decided not to proceed.

Why not a domestic abuse court?

Here we have three disparate sets of proceedings in three different courts: different judges and different court administrations; but the same parties and many of the same facts. We have a brand-new piece of legislation, but no evidence that it will make any attempt to harmonise the procedural disparity between these sets of civil proceedings. And that is before you factor in the possibility of criminal proceedings—again, on much the same facts. The common law, be it noted, is common (no pun intended) to all these sets of proceedings; and to an increasing degree, one statute (DAA 2021) defines them all.

Surely it is time to look through the procedural telescope from the other end, and to try now—with a new statute—to unscramble this morass of different forms of litigation (‘dispute resolution’). One judge could consider all the facts and make findings: what family lawyers call ‘findings of facts hearings’. The parties can then say (on advice, it is to be hoped: legal aid is available subject to means) what statutory or common law remedy they seek. I know that is the wrong way around in conventional litigation terms; but if parties to financial order proceedings can more of less have their own ‘Financial Remedies Court’, why cannot abused parties—often vulnerable women—have their own ‘Domestic Abuse Court’, and their own procedure?

Tentative steps are beginning to be taken to align civil proceedings with family to appoint ‘qualified legal representatives’ (QLRs) for cross-examination of alleged victims by in-person alleged perpetrators. This has been available in criminal courts since 1999 under the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 (YJCEA 1999) (for an introduction to the YJCEA 1999 scheme, see David Burrows, Evidence in Family Proceedings (2016), Chapter 8)). Under s 65, DAA 2021 (in force since 21 July 2022: Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (Commencement No 5 and Transitional Provision) Regulations 2022 (SI 2022/840)) it is intended that provisions in civil and family courts should be made for cross-examination for alleged perpetrators. In what may prove to be an important step of alignment of all civil proceedings, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) has issued guidance for both sets of civil and family proceedings (see Pt 4B of the Matrimonial and Family Proceedings Act 1984 (MFPA 1984) and Pt 7A of the Courts Act 2003 (CA 2003)).

The MoJ has now issued invitations to lawyers to apply to be appointed as a QLR (I have applied). The purpose of the scheme as ‘to ensure that no victim or alleged victim will be directly cross-examined by their abuser or alleged abuser or have to cross-examine their abuser or alleged abuser themselves’. Thus, where cross-examination in person is prohibited, either automatically or following a court direction, DAA 2021 provides for cross-examination by a QLR subject to certain conditions and only where there are no satisfactory alternative means of eliciting the evidence, where the prohibited party has not appointed their own legal representative and where the court considers it to be in the interests of justice to make its own appointment.

Fees will be paid to QLRs, but no travelling expenses. The Lord Chancellor is empowered to deal with this by regulations under s 85L, CA 2003 and s 31X, MFPA 1984. Para 5.2 of the guidance considers this, and a further document describes the fee scheme. It is based on the existing legal aid Family Advocacy Scheme and applies both to civil and family proceedings. An excellent aspect of the scheme is that it is enshrined in statute: that is, it is not left to the vagaries of rule-makers and ‘President’s’ —or any other—non-statutory ‘guidance’. The guidance is statutory.

Towards a definition of domestic abuse

The courts are faced by a variety of shades of common law definition: from Lord Scarman in Davis v Johnson [1979] AC 264 to Sir Andrew McFarlane P with King and Holroyde LJJ (it was a judgment of the court) in Re H-N and others (children) (domestic abuse: finding of fact hearings) [2021] EWCA Civ 448, [2021] All ER (D) 11 (Apr). The lowly PD 12J is the best FPR 2010 rule-makers can offer; and DAA 2021 has a brand-new definition enshrined in statute (see eg in ‘Coercive behaviour in family proceedings’, NLJ, 28 January 2022, p11).

It is unimpressive that in the rule of family breakdown law and procedure when, even for the same two people in two different civil courts—not to mention the criminal courts which deal with domestic abuse cases as well—the term ‘domestic abuse’ can mean different things and engage different procedures and very different judges. This article says that findings of fact by a family court should precede the slotting of the background of the couple, and any children, into a statutory or regulatory straitjacket.

Particularly where the court is dealing with allegations of abuse of parties to a relationship, and often of their children, the making of prompt and efficient decisions on facts must be at a premium. This may seem to many like a radical suggestion. But it is facts which dictate the remedy. If the judge defines the facts first, on the basis of pleadings devoted to facts only, the domestic abuse court process would be so much more effective. Injunction (non-molestation and exclusion) orders, damages, costs claims etc could follow.

The vexed question of whether a fact-finding domestic abuse hearing should be in open court or in private is at large. QBD hearings are open, as are those in the county court and magistrates’ court. The rules say Pt 4, FLA 1996 hearings are in private (FPR 2010 r 10.5). I doubt that that is strictly the law; and a rule cannot change the law. The subject of domestic abuse and open justice must await another day.

David Burrows, NLJ columnist, solicitor advocate, author of Divorce, Dissolution and Separation (Available soon, The Law Society).