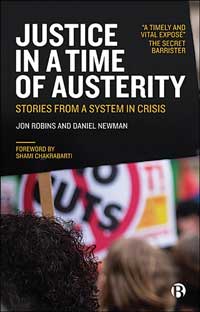

Authors: Jon Robins and Daniel Newman

Publisher: Bristol University Press

ISBN: 978-1529213133

RRP: £19.999 (hardback); £9.99 (paperback)

Be your legal practice never so dry—IP, commercial, conveyancing (I am aware of showing some personal prejudice here)—you should read this book. You will, I hope, be interested in how the law works in less fashionable areas like debt, homelessness, society security and immigration in some of the country’s forgotten places like Bolton, Pontypridd and Ipswich.

The book’s distinctive approach derives from its authors: Jon Robins is an experienced journalist, and Daniel Newman an academic who knows his way around the topic. The authors went about the country in the year before Covid—interviewing lawyers, advisers and their clients. One result is the recognition that it gives to a range of people who have quietly dedicated their lives to their clients. It would be invidious in a review to name any, rather than all. But, this book gives a voice and a recognition to people who are the salt of the earth—and not only in lonely outposts of legal aid and legal advice on the edge of the empire, but also toiling away in other elements of anti-poverty provision, particularly the food banks sadly so much a feature of modern Britain.

Equally reported in their own words are the people seeking help. Certain themes run through the chapters: the impact on individuals of the sheer unfairness of universal credit; the outrageousness of the ‘hostile environment’ for immigrants; the failure of housing policy; the collapse of legal aid; the remoteness of the courts. It is powerful stuff and, of course, the problems are not limited to legal aid. The other strains of modern Britain are manifest. Bolton, for example, is described by its Citizens Advice Bureau chief executive as ‘not quite the Brexit capital of England but not far off’. It is a major dispersal centre for refugees, for which it receives inadequate financial compensation.

Mayor of Manchester Andy Burnham has threatened to withdraw from the dispersal scheme. And no wonder the town’s advice resources are stretched; it has become a race crime hotspot; and the majority of its voters wanted to ‘stick it to the man’ in the Brexit referendum. These things are linked.

Throughout the book, the authors struggle to limit their focus to what they say is its focus: ‘“access to justice”, what it means, and what its absence means for our justice system and for those caught in it’. In part, that is patently because the fundamental problems that people face are the unfairness of the substantive laws that they face. Universal credit, as an example, is little less than a wet dream that manifests the desires of hostile social security administrators over decades. Bit of a problem deciding on benefit payments straightaway? Want to make claimants sweat? Refuse to pay for the first five weeks. Appeals a bit inconvenient? Don’t allow them until a case can be reviewed. Bit difficult to do that on a tight time limit? Give the department discretion to review within any time frame that it considers appropriate. These are, effectively, examples of outrageous breaches of the proper rule of law. No one would accept the equivalent for tax: they are just not acceptable for any government department.

The other problem relates more specifically to the law. What is conveyed by adding ’access’ to ‘justice’?. Is ‘access’ a limiting or an expanding phrase? This debate can taken you into the realms of mediaeval scholasticism. How many angels can sit on the head of a pin? It might be better just to talk about ‘justice for all’ as a policy objective.

But there are some very practical issues that depend on how policy objectives are defined. Covid is absent from this book because it came after the research—though that makes it feel a bit odd. But in a Covid-hit world, where public services are likely to be cut even further, what practical recommendations can be made for the future of legal aid?

Discussion of this issue is where the book ends and where people concerned with the issue must begin. The authors are clear: legal aid in its old form has gone and ain’t coming back. Labour did not impress during its period in office—falling into the barren bureaucratic desert of competitive tenders, rather too often granted to commercially orientated organisations that soon went bust, as the book commendably charts.

We need new thinking, and this book gives a solid base to begin. And it is, indeed, as the authors say, a tribute to ‘the resourcefulness and commitment of those that remain working in social welfare law’. Something that all lawyers should applaud.

Reviewer: Roger Smith, NLJ columnist & former director of Justice