The United Nations was established with the optimistic aim of replacing war between nations by the peaceful settlement of disputes. In the words of the preamble to the UN Charter, its purpose was ‘to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war’. It is painfully obvious that this aim has not been achieved. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) was established in the Hague to adjudicate on disputes between nation states. Ukraine has launched proceedings there, seeking ‘provisional measures’ including ordering the cessation of military operations. A decision is awaited but Russia has already declined to participate. In any event the ICJ has no power to bring individual perpetrators of the most heinous crimes to justice.

International Criminal Court

This gap was filled by the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC) by the Rome Treaty in 1998. More than 120 of the world’s nations signed up to it and the court has been in operation since 2002. Its jurisdiction covers genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Individuals can be prosecuted but not States. Genocide has been alleged but may not be applicable to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Jurisdiction over the crime of aggression has particular limits. It can be pursued only following a decision of the UN Security Council, in which the veto of a permanent member, including Russia, could be used to block a prosecution.

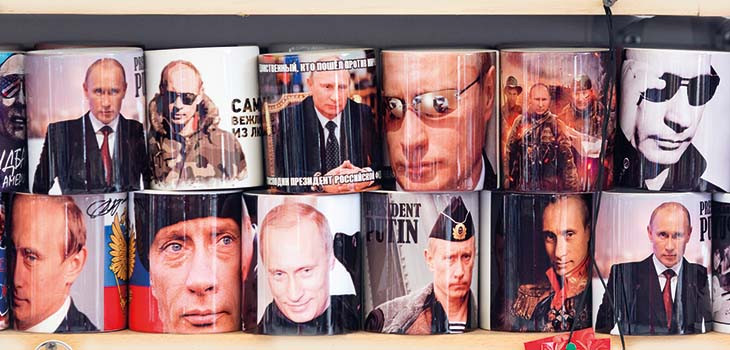

That Russia has committed crimes against humanity and war crimes seems beyond doubt. The recently appointed Prosecutor of the ICC, Karim Khan QC, has already launched an investigation. Vladimir Putin is the obvious defendant. His military commanders and other associates are also vulnerable to prosecution. The Prosecutor has so far acted on his own initiative but his decision has been reinforced by the referral of the matter to the ICC by at least 39 member states including the UK, which has offered full support.

What can the ICC do?

Clearly its intervention is not likely to have an immediate impact. ICC investigations have been notoriously slow and have rarely been followed by effective proceedings before the Court. None of Putin’s previous incursions (as documented by Professor Mark Weller in NLJ, 4 March 2022, p 8) has led to any effective action by the ICC. And the ICC has been criticised for its apparent reluctance to challenge the major world powers who are likely to fight back harder and with greater resources than smaller nations. However, the prompt action and commitment of the new Prosecutor holds out hope of a new impetus in the enforcement of international criminal law.

Yet there are problems ahead for the ICC. Neither Russia nor Ukraine is a signatory to the Rome Treaty and the jurisdiction of the Court over non-members is restricted. Ukraine accepted the jurisdiction of the Court over alleged crimes committed on its territory in 2014 and later extended its acceptance indefinitely. That should be enough to enable the investigation to proceed and establish the basis for a prosecution. Will Russia co-operate? This seems improbable. Yet Putin has always presented his military adventures as lawful and justifiable as self-defence and the legitimate protection of Russian rights. And he has gone to great lengths to prevent the Russian people hearing any alternative view. He could find it unpalatable to leave the case against him uncontested.

The Prosecutor has made clear that he intends an urgent and thorough investigation. He is inviting support from the States Parties and the international community with funding and personnel. An authoritative evaluation of the invasion and of Putin’s claims is important and valuable in itself whether or not a prosecution is mounted.

There are other obstacles to a prosecution. Putin will not surrender himself to the court. Because Russia and Ukraine are not State Parties, it could be contended that the prior consent of the UN Security Council to a prosecution is required. As a permanent member of the Security Council, Russia has a veto over all relevant decisions. Russia already far exceeds the other four permanent members (China, France, the USA and the UK) in its use of the veto. Using it to prevent a trial of its own leaders seems inevitable.

There is a solution―a drastic one. Article 6 of the UN Charter says ‘a member who has persistently violated the Principles contained in the present Charter may be expelled from the Organisation by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council’. The General Assembly of the UN has already voted on 2 March 2022 to condemn the Russian invasion in the strongest possible terms. 141 member states (out of a total of 193) voted in favour and only five against. A two-thirds majority is enough to secure the vote for expulsion. But could a recommendation of the Security Council to expel Russia be blocked by a Russian veto? Surely not.

In the middle of a catastrophic crisis, when innocent civilians are being maimed and murdered in their own homes and streets by Russian artillery, the question seems pettifogging and pedantic. Of course, the immediate priority is not legal but humanitarian, diplomatic and military. Yet the invasion is also an existential threat. Putin has launched an assault on the whole carefully constructed legal framework on which the world (including Russia) has relied since 1945. Central to any safe global future is the commitment to settle disputes peacefully and without resort to force. Those who violate that obligation must be brought to justice. If the ICC cannot do it then a new international tribunal is needed, as proposed by ex-prime minister Gordon Brown.

Sir Geoffrey Bindman QC, NLJ columnist & senior consultant, Bindmans LLP. (www.bindmans.com).