The criminal justice system ought to matter to everyone. It is not just about criminals and their victims, or about those unjustly accused of crimes. If the system can no longer be trusted to deliver its basic functions, then individual freedom, law and order, and the rule of law itself are placed at risk.

To work, all of the system’s parts must work. Unless police, prosecutors, defenders, the courts, the judges and the prisons are all performing their tasks, the chances are that none of them will be fully effective. Even in an adversarial system, their roles ought to be complementary. The skill and efficiency of each part facilitates every other part. Good investigations lead to well-organised prosecutions, which allow focused defences to be presented to efficiently employed judges and juries in well-administered courts, and hence to punishments with the best prospects of rehabilitation.

If any part fails, the other parts have to cope with the consequences of that failure, and the overall effect produces a system like an old boiler producing more smoke than heat. For law and order to be maintained, everything has to work.

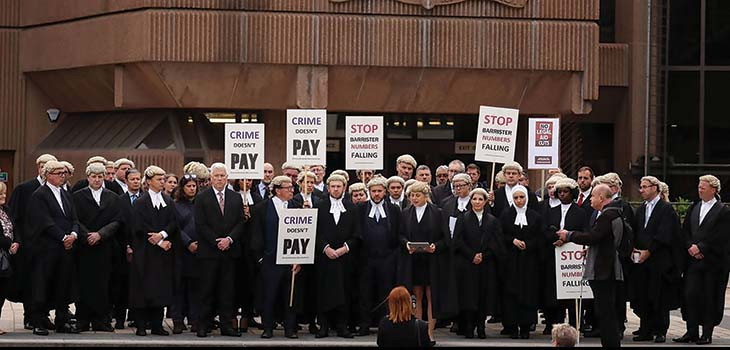

Beyond the picket lines

Images of bewigged barristers ‘on strike’ make an easy story for any journalist. Barristers still have an element of social cache, which makes any photo looking like a picket line seem almost a sociological insight, even if it is not. The 18th century dress adds an element of absurdity, as though it were a placard-waving demonstration of dukes and duchesses in their ceremonial robes of state. The images seem to say: ‘Look! Barristers are really just like train drivers, dockers, health workers or refuse collectors.’ Almost inevitably, this leads to the question of why a barrister should ‘get’ 15% if a nurse must settle for more like 4%.

Although this is an easy way of churning out some news, it should not be the story. The true story is much more complicated and disturbing. It is a story which is not easily susceptible to those old journalistic imperatives of simplification and exaggeration. The real story is not news at all, because it has been building and developing for more than a decade. It is a story of neglect, dilapidation and of political calculation.

If an opinion poll were to be taken, I dare say that neither lawyers nor criminals in general would attract high approval ratings. Giving money to fat-cat lawyers or using large sums to allow criminals to escape justice, if you put it like that, is unlikely to win many elections.

There are, however, few functions of government which are more fundamental than maintaining law and order through an effective criminal justice system; yet it has fallen into such a state of disrepair that it is now possible to contemplate a situation in which it stops working entirely.

Perhaps the drying-up of investigations and prosecutions, interminable delays before trials and outcomes, overwhelmed individuals who have to work in circumstances which make them ashamed, individuals awaiting trials in custody or released back onto the streets, and victims worrying endlessly about when their ordeal will be over, are problems which no government will ever solve.

Once there is no point in reporting crime to the police because they won’t investigate, no point in investigating because there won’t be charges, no point in charging because there are insufficient resources to prosecute, and no point in anything that cannot wait for years for a trial, the only question becomes how deep the spiral can descend. If the system were a donkey, it would by now have been taken into a sanctuary.

The funding of criminal legal aid is but one aspect of a much more generalised problem. The question with which successive governments have unsuccessfully grappled is how to deliver an effective system at proportionate cost.

A criminal justice system is not an optional extra on a menu of government responsibilities. It is the test of any government’s competence and effectiveness. The cost of an effective system would be substantial, but it is something which must be provided by any government. It is not a matter of a policy choice or priorities. Below a minimum standard, it is a question of state failure.

Numbers don’t lie

Nobody doubts that the system has been failing for years, and yet we are probably now further away than ever from an effective system.

There has been no shortage of reports, reviews and proposals in relation to criminal justice over the last two decades. There are too many to mention them all, but they include: the Auld Report (2001); A Fairer Deal for Legal Aid (2005); the Carter Review (2006); Proposals for the Reform of Legal Aid (2010); Transforming Legal Aid (2013); Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates (2013); the Jeffrey Review (2014); the Leveson Report (2015); the Lammy Review (2017); The Law Society Heatmap (2018); Ministry of Justice Proposals for Reforming the Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (2017); The House of Commons Justice Committee Reports (2018 and 2021); and the Criminal Legal Aid Review (2018). Reporting is one thing; acting on reports is quite another.

Most recently, we have the Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid by Sir Christopher Bellamy (now Lord Bellamy) of November 2021. Lord Bellamy’s career was as a competition lawyer and judge, followed by more than ten years as a consultant at Linklaters. In June 2022, he became parliamentary undersecretary of state for justice upon Lord Wolfson’s resignation, and was elevated to the peerage. Although Lord Bellamy’s background and experience are far removed from that of a criminal legal aid practitioner, his report is thoughtful, clear and comprehensive. If there was any doubt previously about what was wrong and why it mattered, that is no longer the case.

The report analyses the evidence of the declining number of criminal legal aid firms. In 2014–15 there were 1,510 firms and in April 2021 there were 1,090: a decline of 27% in seven years. The number of offices available to the public declined in the same period by 20%. A number of larger firms left the market in 2015 when remuneration levels were cut; multi-practice firms have closed their criminal law departments; and older partners have retired without being replaced.

In May 2021, there were only 4,360 specialist criminal duty solicitors distributed patchily across the country. 30 out of 212 schemes have fewer than seven duty solicitors to provide the required 24/7 cover. The average age of duty solicitors, which was rising by one year per year, reached 49 years old in 2019.

In magistrates’ courts, the standard fees were last increased in April 1996 and were actually reduced by 8.75% in 2008. Police station fixed fees in 2021 were around one third less in real terms than in 2008 and materially lower even in cash terms. The report continues in the same vein:

‘6.32 In the Magistrates’ Court, in 1996 preparation was paid at £47.25 per hour in London, and in 2021 is paid at £45.35 per hour; advocacy by a senior solicitor in London was paid at £64.50 per hour in 1996 and is £58.86 per hour in 2021. In real terms, these rates are slightly under 50 per cent less than they were 25 years ago.’

It is possible that fees were higher than necessary in the late 1990s, but by 2006 the Carter Review reported that legal aid firms were already on the edge of profitability. Since then, fees have fallen in real terms by a third.

It is a striking fact that the hourly rate payable to a senior defence solicitor in London in both the magistrates’ and crown courts is less than the average hourly rate put forward by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) to those courts as the hourly cost of its paralegals. Defence rates are 30-55% lower than those considered reasonable by the CPS.

The position of barristers is similar to that of solicitors in terms of declining remuneration and numbers. As individuals, their position is often more difficult than that of solicitors because in private practice they are not salaried and only receive income when eventually fees are paid. Five years after qualification, criminal barristers’ average earnings are £13,000 per annum, which, if they were employees, would be illegal. At the junior end, 40% have given up in the last year. It is hard not to conclude that their ideals of justice and service have been exploited.

Expenditure on criminal legal aid peaked at £1.2bn in 2004–5, but by 2019–20 had fallen to £841m, a decline in real terms of around 43%. A significant explanation for this was a decline in the number of arrests by the police, fewer persons being charged, and limitations on the number of court sitting days.

The reduction in arrests and prosecutions seems unlikely to mean that we have become much more law-abiding—it means that more criminals have been getting away with it. It is now hoped that increases in police numbers and resources will start to reverse this trend. For the system to work, all of its constituent parts, including the police, have to be properly resourced. In 2018–19, £13.3bn was spent on police forces in England and Wales, but this was 16% less in real terms than in 2008–9.

In 2019–20, the CPS received net funding of £567m which appears to be substantially less than its funding of £643m in 2010–11. The CPS reported in July 2021 that as of March 2021, its caseload was 50% higher at 165,157 than it was pre-pandemic. If the prosecution is overstretched, all the other costs of the system, including defence costs, are likely to increase. The system is beset by policy-driven volatility.

Additionally, by the second quarter of 2021, the backlog of cases increased (but not created) by the pandemic, was 364,122 in the magistrates’ court and 60,692 in the crown court. This backlog will require time and huge resources to return even to the troubling pre-pandemic levels.

A sinking ship?

Lord Bellamy recommended that the minimum amount of additional funding required for legal aid firms was £100m, or an overall increase of 15%. For advocates, the figure was £35m which also represented a 15% increase in budget. Both recommendations were on the basis of proposals for fee restructuring. It might be said that even this was like paying the crew a little extra to stay on the sinking ship.

The government has accepted this recommendation, but will implement it in such a way that actual income of practitioners will not increase for many months or years.

In the meantime, demand for legal aid has been managed downwards by failure to link financial eligibility for legal aid to inflation. In real terms, the limit of eligibility is now 24% less than it was in 2008. Unless eligibility keeps pace with current rates of inflation, the proportion of the population able to obtain it in the magistrates’ court will continue to reduce at an even faster rate.

Should criminal practitioners immediately receive the funding recommended by Lord Bellamy as the minimum necessary to keep the show on the road? Of course they should! Successive governments have taken advantage of them for too long. That is the easiest of answers.

So far as the criminal justice system as a whole is concerned, long term reform has remained in a tray marked ‘too difficult’. In the last seven years there have been six Lord Chancellors, including one Liz Truss, who can hardly be criticised for being unable to implement long term reform. The public as a whole have little reason to be concerned about a system most of them will never encounter—there are few votes in fair trials. The challenges in producing an efficient and cost-effective system are immense, but it is the responsibility of governments, without political calculation, to understand the fundamental needs of society and to ensure that they are met. If it takes a strike to encourage that, it will have been worth it.

John Gould is senior partner of Russell-Cooke LLP and author of The Law of Legal Services, Second Edition (2019, LexisNexis) (www.russell-cooke.co.uk).