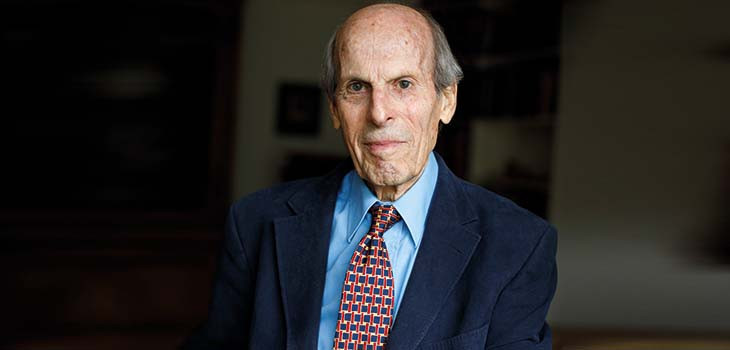

There has been one indomitable presence shining a laser beam into the heart of the justice system, the legal profession, and legal services for more than six decades. And, as he turns 90 next month, Professor Michael Zander’s zeal remains undimmed: he is as focused as ever, writing articles and updating his definitive work on the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (Zander on PACE).

His career took him from newly qualified solicitor to law lecturer, and later professor, which he combined with a forthright role as a legal commentator. This gave him a double platform to challenge what he felt were failings or gaps in the legal world. Unsurprisingly, he became the bête noire of the legal profession. But, after years at daggers drawn, he was ‘astonished and very pleased’ to be put forward by the Bar Council to become an honorary silk in 1997 and, in 2015, received the prestigious Halsbury Lifetime Contribution Award.

Life on the outside

However, Zander never gave up his ‘outsider’ status. While antagonism may have turned into admiration, he has continued to critique legal developments, with his bibliography post-retirement running to 16 pages.

He remains as engaged as ever with the news. Relieved that ‘something sensible’ came out of the previous Lord Chancellor’s conversations with the Criminal Bar over legal aid fees, he stresses: ‘It was a total disgrace that the government allowed fees to collapse to the point where barristers rightly felt they needed to strike.’ His concern now is how Dominic Raab, who returns as Lord Chancellor, will respond to the Law Society’s demand for a similar 15% rise in fees for defence solicitors.

But his focus has never been just inwards. He has also championed those at the receiving end of the legal process, believing it a vital part of his commitment to improving justice that laypeople understand how developments will affect them.

‘More than any other person or group,’ Michael Beloff (now KC) wrote in 1978, ‘he has transformed the perennial but shapeless grumbles about lawyers and their services into an informed national debate.’ But, while he has never hesitated to take on leading figures in the legal or political world, he is nervous about being the ‘subject’. ‘After hundreds of radio and TV interviews, I have never previously been interviewed about myself,’ he admits.

Back to the beginning

Behind an outwardly austere front, there lies a rich family history and an infectious relish in the retelling of the intellectual cut and thrust—and sometimes ‘Byzantine manoeuvrings’—behind some of his most significant achievements.

He and Betsy, his American wife of 57 years, a retired psychiatric social worker, still live in the Highgate home they bought in 1969. Their children, Nicola and Jonathan, co-founders of a consultancy specialising in transformational change, were born there. It is also close to Arsenal—the team he started supporting at ten and he now delights in sharing that passion with the next two generations.

So, what led him to become Beloff’s ‘unlicensed gadfly’, constantly challenging the status quo?

He was born in Berlin in 1932. His father Dr Walter Zander, a lawyer, and his mother Margarete Magnus, a secretary and translator, brought the family to England in 1937 to escape Hitler. Michael’s three younger siblings also went on to become leaders in medicine (Luke), art (Angelica) and music (Benjamin). The family settled in Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire.

From 1938 to 1946, he went to the local Gayhurst Preparatory School. While he had a place to go on to public school, the 13-year-old Michael chose instead to go to the Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe. ‘I later discovered I was the first boy ever to go to the local grammar school from my prep school,’ he says. ‘But I thought it was the responsible thing to do and it made sense financially.

‘My parents, a little reluctantly, agreed. But it was entirely the right choice. It was an excellent school and I did very well academically and in sport.’

It was also an early indication that he was never going to be someone who followed the crowd. And it led to his first publication—a letter in the Times Educational Supplement—‘complaining bitterly’ that private school holidays were longer than his.

Cambridge was the ‘obvious’ next step because his headmaster had a connection with Jesus College. After visiting, he was told to ‘go away, do your exams and come back’. He recalls: ‘I eventually got a scholarship but that was the entire entry process!’ In the school holidays and university vacations he took a variety of jobs, including driving an ice-cream delivery van and, later, taking tourists around Europe as a tour leader on ‘thirteen-day, seven countries’ coach trips.

At Cambridge, he was, by his own account, an ‘entirely unrebellious’ student. He was so bored by the way law was taught as a ‘self-contained, abstract system of thought separated from the hopes, fears and interests of human beings’ that he considered switching to anthropology and archaeology, despite coming top of his year. He was persuaded to stick with law and finished his undergraduate degree with a double first honours degree in law, followed by first class honours in his LLB specialising in international law.

As he is quick to admit, that ‘unadventurous’ young graduate would have been astonished if someone had predicted then that he would become the scourge of what he came to see as a complacent legal profession and a justice system failing many of those it should have been helping. The trigger turned out to be two transformational years in America, the first one at Harvard on a Fulbright Scholarship and a scholarship from the Law School. He was advised to take a taught LLM, again in international law, to experience its famous teaching methods which, unlike Cambridge, focused on the social, economic, political, and philosophical implications of legal problems.

‘It was a revelation,’ he says. ‘It made my studies meaningful and I got a better sense of what teaching law could be about.’

He followed this with a year doing ‘heavy-duty’ litigation at one of the ‘great’ Wall Street law firms—Sullivan & Cromwell—where he saw first-hand the contrast between the split English profession and the unified American profession. ‘I came to the conclusion that the American system was better,’ he says. ‘I remember giving a talk to the litigation department where I described what I saw as some of the problems with the English system. I said something like “I am going to go back and do something about it”. It was the first time I heard myself talking about a career in changing the system.’

Rocking the boat

He was 27 when he returned to England in 1959. Influenced by his American experience, he switched from pursuing a career at the Bar to become a solicitor, because he saw the benefit of having a direct relationship with his clients. He became a solicitors’ articled clerk with Ashurst Morris Crisp & Co, on £800p/a. It was during his articles that his firm effectively released him to work on Tony Benn’s Election Court case to remain an MP after succeeding to the Stansgate peerage.

But he increasingly felt teaching and writing would allow him to study issues he had identified, rather than those put to him by his clients. He went to talk to the London School of Economics (LSE)—the only university he considered. He was strongly advised to complete his qualification first, given his growing interest in writing critically about the legal profession. ‘It was bad enough to be accused of being a mere academic,’ he says. ‘Not being a qualified barrister or solicitor would have been seen as further justification for disregard.’

He took the advice and qualified as a solicitor in 1962 and worked for another year before joining the LSE as an assistant lecturer, becoming a professor in 1977. He was to stay there 35 years until he had to retire at 65 in 1998.

He certainly could not have chosen a redder flag than fusion of the two sides of the profession for his first target. He wrote and spoke on the subject which he developed in his first book, Lawyers and the Public Interest (1968), a severe critique of the array of monopolies and restrictive practices maintained at the time by, or for, the legal profession.‘The book was not well received,’ he says, with wry understatement. Indeed, both sides of the profession were enraged. A review in the NLJ said: ‘If there is a prize for the legal hackle-raiser of 1968 this book may well win it.’

Was he ever daunted by the fury he caused? ‘I never thought of it as courageous,’ he says. ‘I played a particular role, the profession was playing its role and we had fierce debates. I enjoyed it very much.’

He has also always kept an open mind. He gave up the fight for fusion once it became clear it was not going to happen. Subsequently, most of the restrictive practices were abolished, and he says he came to see there were benefits for clients in having a split profession.

Man of his word

For those who only know him through his forthright writing and expect an abrasive critic, he confounds expectations by being diffident and softly-spoken. He was formal rather than ‘matey’ with his LSE students, but he sought to bring out the best in them by inspiring independent thinking. His book Cases and Materials on the English Legal System (now in its 10th edition) broke new ground by including his own detailed commentary which put the cases in context.

Alongside his scholarly writing and lecturing, Zander was also building his profile as a legal commentator, writing over 1,400 articles during his 25 years as The Guardian’s legal correspondent. He also wrote as Justinian for The Financial Times and continues to write for the NLJ, 55 years after it published his first article in 1967.

He went freelance in 1988—even writing once for The Daily Mail, he admits with a smile—after being unceremoniously dropped by The Guardian. ‘The first I knew I was no longer legal correspondent was when I saw a piece by-lined by my successor!’

What his LSE colleagues thought of his dual career remained a mystery. He would have a by-lined main feature in the paper in the morning. But when he joined his academic colleagues round the lunch table, no one would mention it. ‘It was comical,’ he remembers.

But, on other fronts, his articles lit fuses that led to two royal commissions in consecutive years and significant reforms (see below).

The first was sparked by Zander’s study ‘Costs in Crown Courts—a study of lawyers’ fees paid out of public funds’ (Criminal Law Review, 1976). It raised the question as to whether they were too high—somewhat ironic, he says, in light of today’s battles over fees.

He sent a pre-publication copy to Bernard Levin, the acerbic Times columnist, who saved a special venom for lawyers. On a flight back from America in January 1976, Zander picked up The Times to find Levin’s excoriating article based on his study. On the day of his return, Jack Ashley MP used the study to call for a royal commission and Zander went straight into the TV studios for a BBC debate with the then Bar chair Sir Peter Rawlinson.

This stung the Lord Chancellor Lord Elwyn-Jones to make an immediate and negative reply. Zander mustered an impressive campaign behind the scenes in No 10 and the Home Office, and in the media. As the pressure built, the Law Society and Bar Council came to accept the case for an inquiry. Five weeks after Levin’s article, Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced the Benson Royal Commission on Legal Services.

It is clear Zander enjoyed the machinations involved. ‘Absolutely—to put it at its trivial level, it was great fun,’ he says. ‘But it was a very serious business. The resulting recommendations were a disappointment in some respects. Many of the things I suggested were rejected but, in the end, both sides of the profession found they could live with the result, so it was a win-win.’

Picking up the PACE

History repeated itself just a year later. In the May 1977 issue of the Criminal Law Review, Zander published ‘The Criminal Process—a Subject Ripe for a Major Enquiry’. He sent the article to the Home Secretary’s political adviser and later discussed it with him. The Philips Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure was announced five weeks later. It led to two major pieces of legislation—PACE 1984 and the Crown Prosecution Act of 1985 which established the Crown Prosecution Service.

Little did he know that his ten-page article would turn into his main work for the next 40 years. He published his first book on PACE in 1986 to coincide with it coming into force. It ran to 300 pages. By the 6th edition, Zander on PACE ran to more than 1,000 pages. The 9th edition is due out in February.

The major change this time is around pre-charge bail. The government has rightly done a U-turn, he says, in reversing the controversial 2017 presumption of release without bail and the resulting introduction of released under investigation. ‘The unfortunate effect was a predictable collapse in pre-charge bail,’ he notes. ‘The police love it because it doesn’t involve any paperwork, controls or time limits. The government hopes the current change will restore bail as a proper part of the system for the benefit of victims. However, I am fearful it will not as the police have become so wedded to it, I think it will be difficult to drag them back to the bail system.’

While Zander likes to work alone, he led the way in legal academia by including empirical research in his studies. In 1991, he was persuaded for the first time to become an ‘insider’ and join the Runciman Royal Commission on Criminal Justice, set up after a series of high-profile miscarriages of justice. This led to his most ambitious research project involving all the participants—from judges to jurors—in 3,000 crown court cases completed over a two-week period. The resulting 22,000 questionnaires provided information which helped inform the commission’s recommendations. ‘Perhaps the most surprising finding was how positive the 8,000 or so jurors were about the trial process,’ he recalls.

It was a ‘wonderful, intense experience’, he says. But combining the commission role with running the crown court study and teaching full-time meant it came at a ‘grievous cost’ to family life.

The commission’s 352 recommendations were largely uncontroversial and implemented. But Zander still played an ‘outsider role’—writing a 14-page dissent, much to the chairman’s dismay, on three topics: advance disclosure by the defence; the pre-trial process; and the Court of Appeal’s approach to unacceptable conduct by the prosecution.

No greater authority

In a similar vein, he enjoyed being at the heart of high-profile political debates and campaigns, but was never tempted to become a professional politician. An active member of the Society of Labour Lawyers, he was one of the 100 signatories who supported the creation of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1981. He was involved in the Social Democratic Lawyers but took no part once the SDP morphed into the Liberal Democrats.

In 2010, Zander was awarded the Honorary Doctorate of Laws by King’s College, London. The citation said he had made ‘outstanding contributions in both the academic and public spheres. There is no greater authority in the fields to which he has devoted himself: criminal procedure, civil procedure, legal system, legal profession and legal services. ... The central mission of his professional life has been to make the justice system work better.’

That sentiment continues to this day. After an intense period updating his PACE book and finishing some articles, he is at something of a juncture. ‘I am not quite sure what comes next. We shall have to see.’ But he has no plans to stop writing. ‘I do not regard 90 as a disqualification—I have no intention of bowing out yet.’

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance legal journalist.

Zander on Zander

Michael Zander’s mission throughout his professional life has been to make the justice system work better, and his achievements are legion—but what changes have brought him the most satisfaction?

He singles out three developments: law centres; the duty solicitor scheme in magistrates’ courts; and the Bill of Rights that became the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA 1998)

Justice for all

Zander was in America in 1964 on a Ford Foundation grant looking into the development of neighbourhood law firms as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s ‘war on poverty’. He became the first person in the UK to write about the idea, and was chief draftsman of the pamphlet Justice for All, published in 1968 by the Society of Labour Lawyers, which recommended setting up ‘local legal centres’ in poor areas. The first law centre opened in North Kensington in June 1970 through the initiative of local lawyers, led by Peter Kandler.

‘Law centres have become a very significant part of the structure of legal services,’ he says. ‘I just wish there were more as they do a good job.’

Call of duty

In 1969, a research project he undertook with students led to his article ‘Unrepresented Defendants in the Criminal Courts’ in the Criminal Law Review.

‘Contrary to official wisdom at the time, the study found that the majority of defendants sentenced to imprisonment by magistrates were unrepresented,’ he says.

He was the chief author of JUSTICE’s subsequent 1971 pamphlet The Unrepresented Defendant in the Magistrates’ Court. The following year, local lawyers, working through their local law society, set up the first duty solicitor scheme in Bristol. By 1977 that had grown to 79 and it became a national scheme operating in all magistrates’ courts under the Legal Aid Act 1982.

Standing the test of time

In 1975, Zander published his pamphlet A Bill of Rights? and played a key role in the campaign to persuade senior members of the Labour Party to accept the need to incorporate the European Convention on Human Rights into UK legislation.

‘It was a huge triumph and led to a workable and sensible piece of legislation,’ he recalls. ‘The Act has been a huge power for good and I was extremely unhappy with the attempt by Dominic Raab, the last time he was Lord Chancellor, to undo some of the benefits. I was delighted when the government halted his Bill. I am very disappointed that he has been re-appointed and very concerned that his wretched British Bill of Rights may now go forward.’

Getting institutions to move is hard work. ‘You have to pursue ideas energetically and when they say no, you go on and when they say no again, you go on again,’ he says. ‘Sometimes you get the result you want—but you also need to know when to give up graciously.’